When he was 14 years old, Bobby DelVecchio left his fifth-floor walk-up in the Bronx for the subway. He jumped the turnstiles for a train to midtown Manhattan, Madison Square Garden, to be exact.

The rodeo was coming to town. And Bobby had scored a gig shining shoes and boots.

The money from the shoe-shine job would pay for Bobby’s entry fees in a junior bull riding across the river in New Jersey.

Teenage boys can go through sizable transitions, and this kid from 182nd Street was amid a wild one. He was changing from a rambunctious boy playing stickball and swiping hubcaps in the confines of the concrete jungle to a blossoming cowboy set to escape to wide-open spaces and pursue big dreams.

Following that rodeo at the Garden, Bobby would soon leave home on a highly improbable road taking him to far corners of the country. He became one of the world’s most famous and beloved rodeo stars… and then a founder of a new bull riding organization that would grow beyond everyone’s imagination.

Hailing from the mean streets of a rough-and-tumble borough, brazen Bobby had chosen the toughest, most audacious athletic task imaginable – riding bulls.

As animals went, he was quite familiar with the common New York brown rat, but he hadn’t seen a cow or a bull in person until he was 13, out in Jersey.

Before that, DelVecchio learned to ride horses at the Pelham Park Riding Academy. He was brought there by his dad, who worked in the GM auto plant up north in Tarrytown, New York, and had a love for horses.

There, where steamy streets gave way to a horse trail snaking through marshlands and woods, DelVecchio met a retired rodeo cowboy who took him to a weekly rodeo in Cowtown, New Jersey.

The fearless teenager tried riding a bull. He lasted only a few seconds. Angry at being thrown, he tried again. And again.

“For $10, you could get on all the bulls you wanted,” DelVecchio said.

He never thought anything was as wild as his neighborhood. This was wilder. It was easy to get hooked.

“Riding bulls and being in rodeo was like watching something right out of American history,” DelVecchio said.

Not much fazes overstimulated New Yorkers. But neighbors would stop in their tracks at the darndest sight: that Bobby DelVecchio boy out on the rickety fire escape with his rope, practicing bull riding moves.

The kid could ride, and it didn’t take him long to decide this would be his life. He was 15 years old when he quit school to become the youngest professional cardholder in the PRCA (Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association).

“Once I got a taste of rodeo, it was, ‘Go west, young man,’” DelVecchio said. “And I did.”

DelVecchio would compete in 150-175 rodeos a year, eventually flying his own plane to make the 300-days-a-year travel easier. He would perform in a special rodeo exhibition for President Reagan in 1983 at the Capital Center in Landover, Maryland (Bobby won), and appear on the TV show Dallas.

Bobby was cocky. While some riders would go into a trance to prepare for their bull, he’d flirt with the girls and drink Cokes.

The Italian swagger was backed with big rides and event buckles.

The press loved Bobby almost as much as the women did.

They’d say a cowboy was born where the cockroaches would roam.

They’d write that he was the main star in a real spaghetti Western.

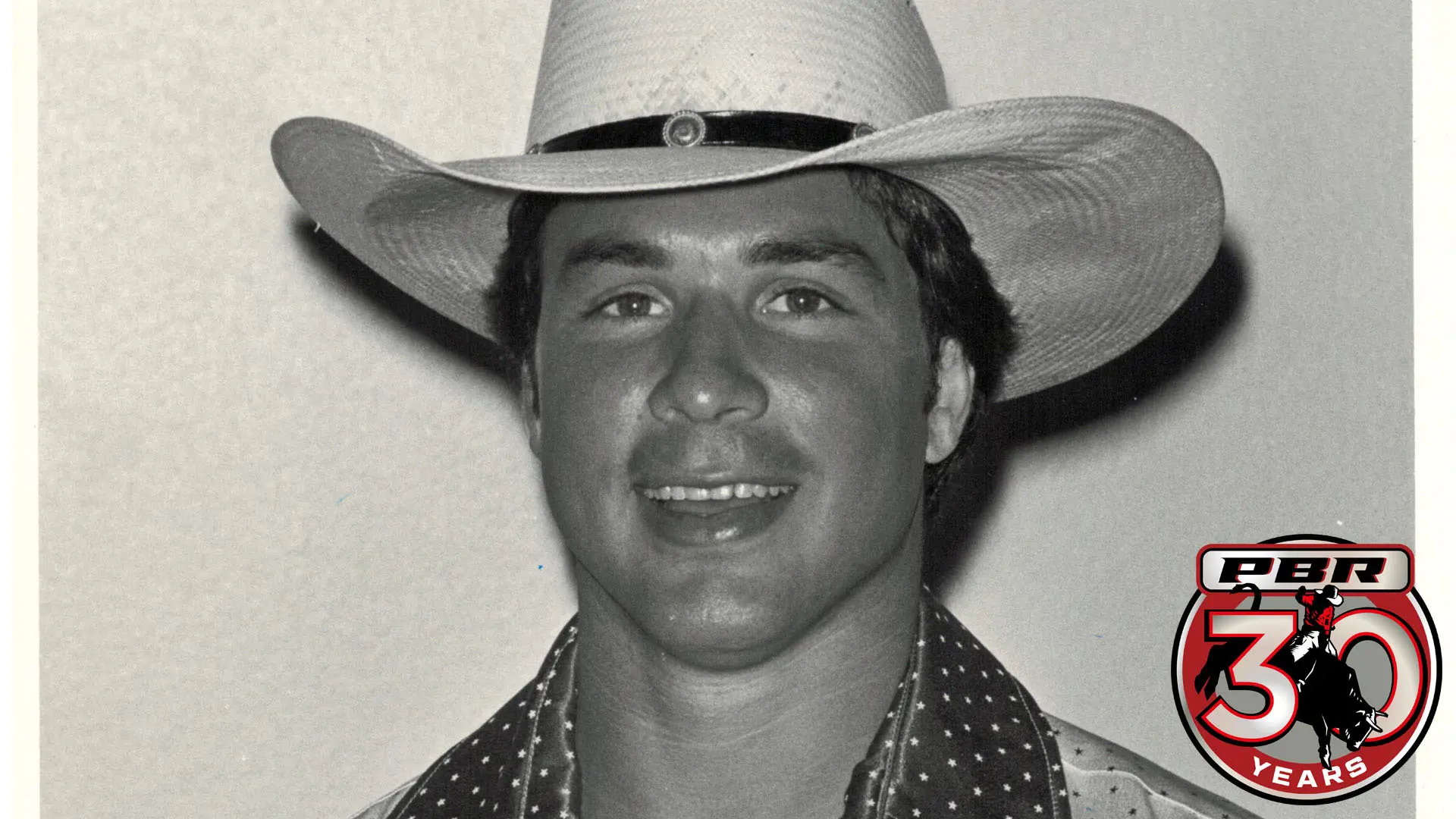

The real-life urban cowboy was what they call good copy. He’d lay claim to nearly as many nicknames as event titles.

To some, he was “the Concrete Cowboy.” To others, he was “The Kissing Cowboy” for the way he’d blow kisses to the gals in the grandstands after making the whistle.

Bobby’s undeniable radiance was making rodeo a lot more fun. His colorful, charismatic magnetism made him a fan favorite. The crowd loved him, and he loved them back.

Some writers called him “the John McEnroe of rodeo” – a comparison to the brash tennis player from the across-the-bridge borough of Queens who took the tennis world by storm just as Bobby, with his flashy red chaps, rhinestone-emblazoned shirts, smoldering good looks, self-described “Dago charm,” and crowd kissing, was upending the rodeo world, nearly winning the world championship three times.

On the heels of the hit film “Rocky” came the next nickname, “The Italian Stallion.”

DelVecchio would lose his sarcasm-slinging “New Yawk” accent for a Texas-Oklahoma drawl.

But he’d always credit his formidable city years for the mental toughness it takes to get on a 1,800-pound bull bred to buck after he’d walloped you in the face the night before.

“Growing up in New York made me a better bull rider,” DelVecchio said. “A tough environment only makes you tougher.”

At the tail end of his career, in 1992, DelVecchio was one of 20 rodeo cowboys who invested $1,000 apiece to form a standalone bull riding organization, Professional Bull Riders (PBR). He retired from riding soon after the PBR started to gain popularity.

Bobby was inducted into the PBR Ring of Honor and the Rodeo Hall of Fame. And he’s still intriguing to anyone who loves a good story.

A major motion picture is now in development, charting the epic 1982 season when Bronx-born Bobby and little Charlie Sampson from Watts – two fish-out-of-water newcomers to an insular sport – took rodeo by storm, finishing 1-2 in the world, with Sampson becoming the first Black bull rider to win a world title.

“Charlie and me, we weren’t traditional cowboys who would grow up in the culture,” DelVecchio said. “It was odd to have two guys, one from one coast, one from the other, going into the middle of the country. We developed a great friendship. We showed up from different parts of the country and started kicking ass. And the rest of the guys didn’t like it. Especially when we started taking their money.”

Back when he was 14, practicing out on the Bronx fire escape, DelVecchio shined boots at Madison Square Garden when the rodeo came to town. On Friday night, Jan. 6, he will help the sport he co-founded celebrate its 30th anniversary during a pre-show ceremony inside MSG. The show airs live at 6:30 p.m. ET on RidePass on Pluto TV.

As a rodeo cowboy, Bobby DelVecchio loved the sport, the adrenaline, the adulation, and most of all, life.

He still does, and it’s impossible not to love him back.

Andrew Giangola is the author of Love & Try: Stories of Gratitude and Grit in Professional Bull Riding, available at amazon.com and PBRShop.com, with proceeds benefitting injured bull riders.