07.16.11 - Heroes & Legends

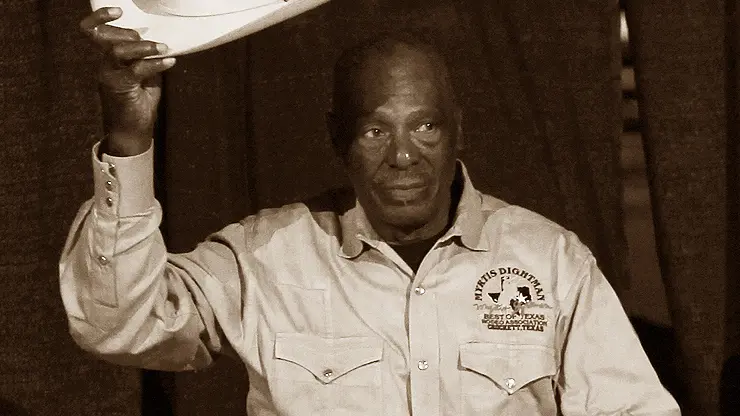

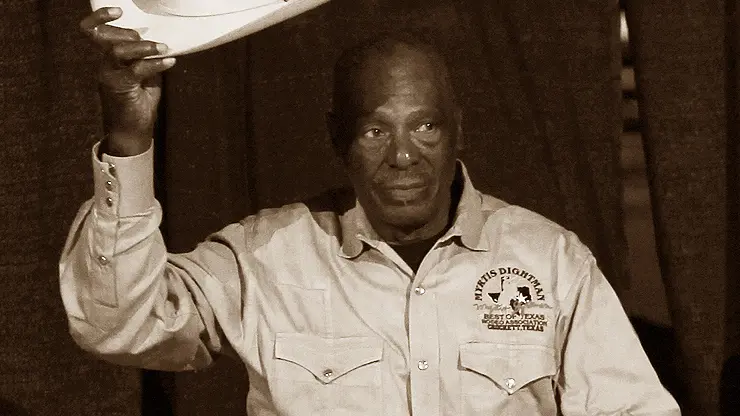

Heroes & Legends: Myrtis Dightman

Forty years from his Calgary win, a trailblazing black cowboy still inspires

By PBR

Forty years ago, Myrtis Dightman won the Calgary Stampede.

He remembers Calgary as a wonderful place - not just because he had never been there, but because of the warm reception he received.

Dightman, a black man, wasn't always welcome when he came to ride bulls.

The 76-year-old has been described as the Jackie Robinson of professional bull riding. He was the first African-American to qualify for the National Finals Rodeo, and in 2003, was inducted into the PBR Ring of Honor.

"I just couldn't believe it," he said of his Calgary experience. "If I needed anything, they would help me. People in Calgary are real nice people. They would take me in and let me stay with them. The guys that were living up there would take me over to their house and let me stay right with them."

That hospitality was in stark contrast to most other rodeos.

Despite his incredible talent, Dightman was often made to ride after the events were over and the crowds had left.

"It wasn't always easy," he said. "It wasn't the rodeo people. It was the stock contractors." Some bull men weren't thrilled at the idea of a black man covering their prized stock.

Nine-time World Champion Ty Murray said that because of the prejudice he encountered, Dightman probably only won a third of what he was due.

Quite often, when the draw was announced, Dightman would be matched up with bulls that had never been ridden. Only years later did he learn that those draws had been fixed.

"I didn't know. I thought that's the way it was drawn up," he explained, before laughing. "It didn't make a difference. I won anyhow."

Dightman, like his late father O.D., grew up working cattle on a ranch outside his hometown of Crockett, Texas.

The family never owned a ranch of their own. His father was a hired laborer, and taught his son what it meant to earn his keep. The younger Dightman was rewarded with the opportunity to take part in trail rides.

Later on, he started working as a bullfighter before deciding on a bull riding career.

He faced the racism with his chin held high. It wasn't that he was particularly tolerant, but he was determined to win over doubters and detractors by proving he had the same characteristics as any other American cowboy.

He remembers receiving a call once from a rodeo secretary, asking if he had encountered any problems.

Surprised by inquiry, he replied, "No ma'am."

He was confused when she asked about when he rode, and if anyone else rode with him after the events had concluded.

"After that, if they held me back, they had to hold three white guys back," he said. "That's what broke it."

Ty Murray and former NFL great Walt Garrison, both of whom have befriended Dightman and his family, are saddened by the stories they've heard about Dightman's challenges, and have worked to see that the he is recognized for his accomplishments.

"In every account that I've ever been told, Myrtis always got hosed just because he was a black guy," Murray said.

Despite the obstacles, Dightman twice finished third in the PRCA world standings, and in addition to the Calgary Stampede, he also won Cheyenne Frontier Days.

But according to Dightman, his finest hour as a professional bull rider came long after he finished his career.

In 2003, Murray contacted Dightman's son with news that the PBR planned to induct his father into the Ring of Honor. But as far as Myrtis knew, they had merely invited him out to Las Vegas for an event.

"I said, 'OK,'" he explained. "I wondered where he got the money from, and Ty Murray still never told me anything. They just said, 'Come on, let's go to the Finals.' They kept me in the dark."

That night, Dightman listened to Murray address the crowd. He talked about a great bull rider who had never gotten what he deserved.

"I was looking around and thinking, 'Who is he talking about?'" Dightman said. "Then he said, 'Myrtis Dightman.' I could have cried.

"I put that ring on and I never did take it off."

Two months ago, the much-loved Dightman was honored with a bronze statue in his hometown - a project that was spearheaded by Garrison. It was an event that, according to Dightman, tongue firmly planted in cheek, "even the white people enjoyed."

"It's nice to see Myrtis get the recognition," Murray said.

To acknowledge the 40-year anniversary of his win in Calgary, Dightman had hoped to visit the event for the first time since.

But his mother Ada Lee Polk, 95, is in a nursing home, and his older sister Early Mae, 79, passed away on Wednesday.

"I just hate that I couldn't make it this year," said Dightman. "I would have gone to Calgary this year, but the good Lord gave me something else to do.

"You know, He's kind of in charge of everything."

- by Keith Ryan Cartwright